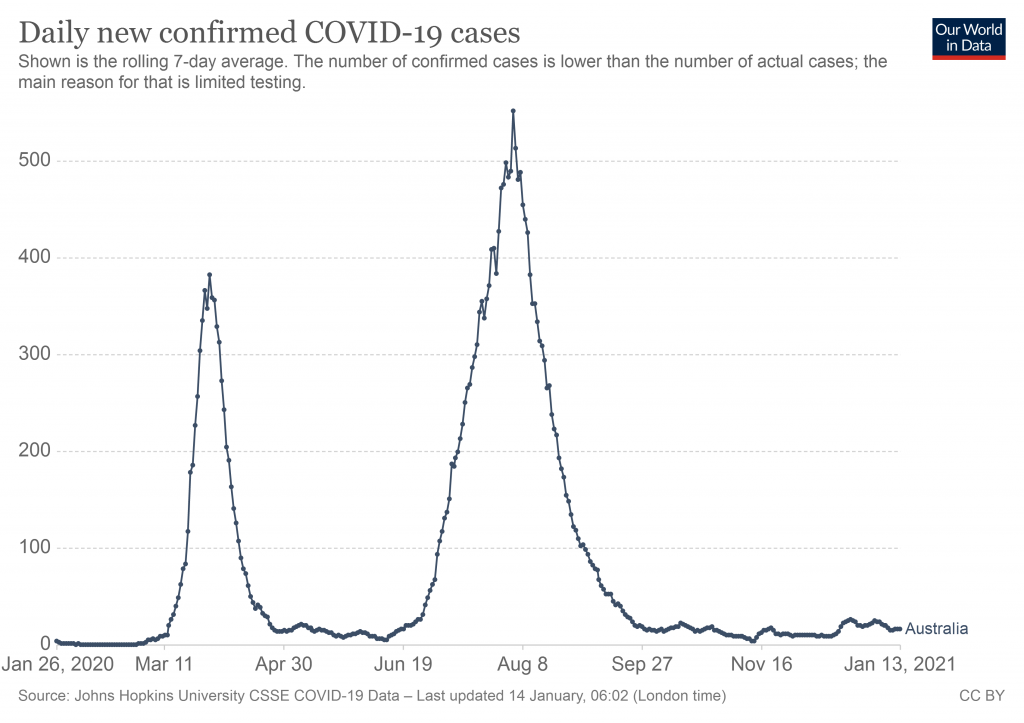

No. Look at this graph.

Australia has largely suppressed COVID-19, but is still performing tens of thousands of tests per day (just over half a million in the last week). Despite this, the number of positive tests is close to zero.

Well, that was an easy question to answer. But let’s take a closer look at how PCR tests work, and how this idea that many may be false positives came about.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) describes a technique to create hundreds of thousands of copies of a piece of DNA, so that there is enough to analyse. It’s combined with another technique called reverse transcription, which converts RNA into DNA. This first step is necessary, because the virus which causes COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) is a RNA virus. Both RNA and DNA are types of genetic material.

The end result, is that we have a technique called a reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test, which allows us to detect people who might be infected with SARS-CoV-2.

But tests usually aren’t perfect. They don’t always manage to detect what they are looking for, and they might also mistakenly detect something they are not looking for. These two concepts are called sensitivity and specificity.

Sensitivity is a measure of how well a test detects what it is meant to detect. For example, let’s say we had 10 samples which are known to contain a virus. A sensitivity of 90% would mean we would correctly classify 9 out of 10 samples (90%) as positive, and would incorrectly classify 1 of the 10 samples as negative (a false negative).

Specificity is a measure of how specific the test is. Does it only detect what we are looking for, or does it mistakenly detect other things as well? Let’s suppose we have 10 samples which we know are virus-free. If our test had a specificity of 100%, it would correctly classify all 10 as negative. But if our test had a specificity of only 50%, it would incorrectly classify 5 of the samples as positive (false positives).

So, for a test to be useful, we want it to have high sensitivity (few false negatives) and high specificity (few false positives). How good are the current tests for SARS-CoV-2?

Researchers have evaluated the performance of some of the most commonly used tests, and found the majority had a sensitivity and specificity very close to 100%.

The accuracy can be further improved by running more than one kind of test. In Australia, two or more tests are typically performed, each looking for a different piece of the genetic code of SARS-CoV-2. By considering the result of more than one test, false positives become even more unlikely.

Another way to estimate how common false positives might be, is to compare the number of tests conducted each day with the number of positive test results. For example, on the day I wrote this piece, 63,170 tests had been performed in the last 24 hours in Australia, and 10 cases had been detected.

If we were to assume a worst case scenario in which all of the positive test results were in fact false positives, then the proportion of false positives would be 10 divided by 63,170. That works out to be 0.016%.

Clearly, false positives are very uncommon.

A much bigger issue is the occurrence of false negatives. Although most tests have a sensitivity of 100% under specific laboratory conditions, sensitivity may actually be a lot lower in practice.

For example, if an infected person is tested too soon after exposure, or if a swab of the nose and throat isn’t thorough enough, there may not be enough virus present in the sample for the test to detect.

For this reason, a negative test result can’t guarantee that someone isn’t infected. Anyone who has been exposed to someone with COVID-19 should continue to quarantine, even if they receive a negative test result.

In conclusion, we can be confident that a positive test result means that someone really has been infected with SARS-CoV-2. But we have to be much more careful with negative test results.